by Xiao Ming

Introduction

I first met Xia Chunlin over a decade ago while I was conducting research, for an essay I was writing at the time, about the mass killings that occurred during the Cultural Revolution in Guangxi province. He gave me access to a huge amount of historical materials relating to the Pingle Massacre. He also provided me with his own eyewitness testimony. Since then we’ve been in contact often.

Recently I had the opportunity to meet up with him again. He spoke at length about his family’s terrifying experiences during the Cultural Revolution. He hoped that I’d be able to turn his memories into an essay, so that this bloody massacre is never forgotten.

Background

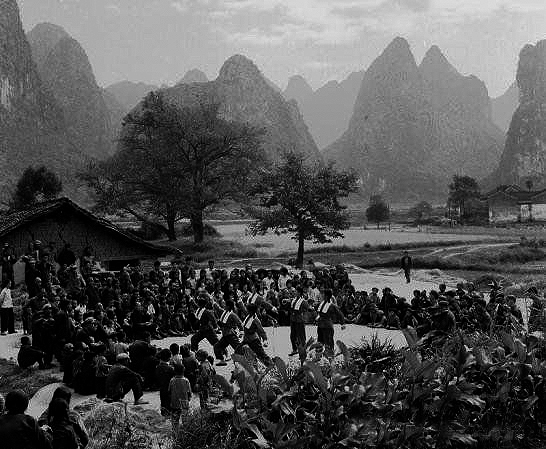

Pingle Country is located approximately 120 kilometers southwest of the city of Guilin. The Lijiang River flowing from Guilin, together with the Gongcheng and Li Pu rivers merge in Pingle, becoming the Guijiang River, which winds its way down through the province to the city of Wuzhou where it joins the Xijiang River, which, via Guangdong, ultimately drains into the South China Sea. During the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), the area we now call Pingle was part of Guilin county; it emerged as its own county during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), enjoying a history of more than 1700 years.

The residents of Pingle are primarily Han, accounting for about 83% of the population. The remaining 17% is comprised of ethnic minorities from the Yao, Zhuang, and Hui peoples. By the 20th century, Pingle was relatively well developed in terms of commerce and culture, more advanced than neighboring counties due to its convenient land and water transport routes, a part of the civilized world.

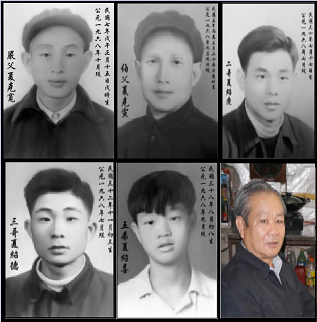

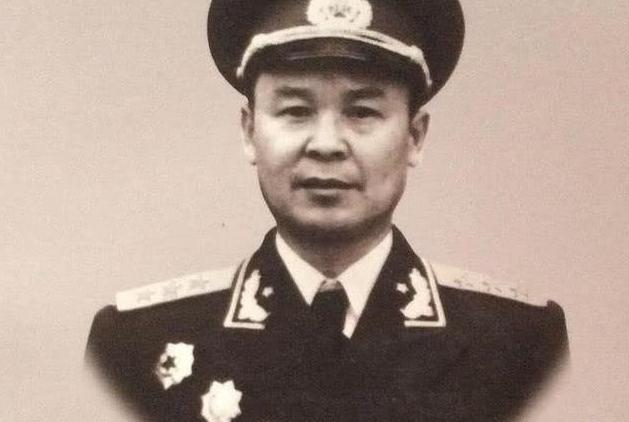

However, in 1968, during the Cultural Revolution, an explosion of savage violence rocked the county. Egged on by Mao’s calls to crush ideological heretics, and under the direction of Wei Guoqing, the First Secretary of the Party Committee of Guangxi Province, the Chairman of the Guangxi Revolutionary Committee and the Political Commissar of the Guangxi Military Region, and the provincial authorities, Guangxi experienced large scale slaughter which left close to 100,000 people dead. In Xia Chunlin’s family, a total of seven male relatives were murdered. Five members of his own household, and two members of his extended family. Xiao Chunlin was the target of numerous traumatic struggle sessions, narrowly avoiding the same fate of his less fortunate relatives.

Xia Chunlin’s Family on the Eve of the Cultural Revolution

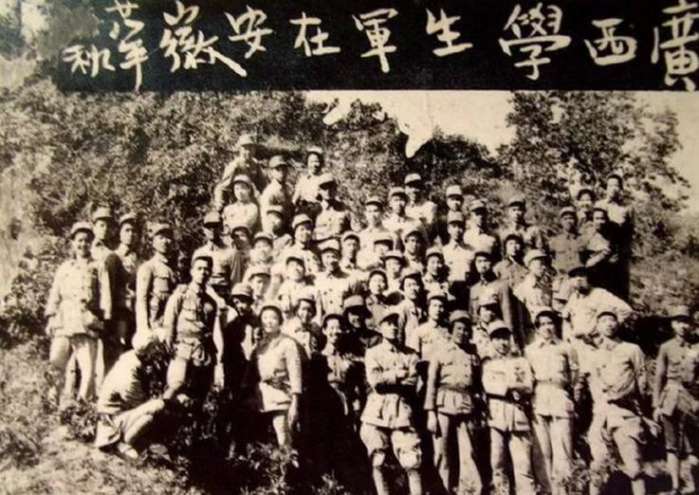

The Xia clan of Pingle lived in the villages of Dafaxiang, Canbancun and Xiajiatun. Ethnically Han, their forefathers made a meagre living tilling the fields from sunrise to sunset. Xia Chunlin’s household was located in Xiajiatun village. In the last days of the Qing dynasty, the family moved to Pingle from Hengnan county in Hunan province. In the early days of Communist rule, the family had a good reputation in the village, due to his father’s elder brother, Xia Jingsheng, who, after fighting against the Japanese invaders as part of the Guangxi Student Army, joined the Communist Party in 1938. After the Communist government was established in 1949, he became the first appointed district chief of the village of Dafaxiang. Xia Chunlin’s father, Xia Kekuan, was an honest, hardworking peasant, after 1950, he also served as a village captain, working dilligently for the Party during the campaigns to eradicate banditry and implement land reform.

As well as serving as district chief of the village of Dafaxiang, Xia Jingsheng worked at a hardware company in the county seat, Pingle Town. His wife was named Wang Lichu, their children died in infancy. As well as Wang Lichu, Xia Chunlin had two other aunts, his father’s sisters, Xia Lansu and Xia Yukun. Aunt Lansu lived in the county seat, a member of the people’s militia, she was childless. Aunt Yukun lived with her husband in the neighboring county of Gongcheng.

His father, Xia Kekuan, had five children. Xia Chunlin’s elder sister, Xia Yusu, was married to a worker from geological prospecting team. On the eve of the Cultural Revolution, she moved to Sichuan province, when her husband was relocated there to provide support for the Third Front development program. Xia Chunlin worked at a rice factory in Pingle Town, while his two elder brothers Xia Shaoqing and Xia Shaode worked together nearby at a freight company. His younger brother, Xia Shaoxi was in the third grade at the local junior middle school when the Cultural Revolution began.

Persecution and Wrongful Imprisonment

In 1951, during the Land Reform Movement, no landlord could be found to single out and punish in the village of Xiajiatun, the home of Xia Chunlin’s family, because the residents were all destitute peasant farmers. However the Land Reform team insisted that in order to rouse up the farmers and get them to participate in the campaign, they needed to classify someone as a landlord, regardless of their true status. Xia Chunlin’s father, Xia Kekuan, a member of the Village’s Farmers Association, and village captain of the People’s Militia, spoke out against this arbitrary and illogical persecution, consequently earning the animus of the Land Reform team. Xia Jingsheng supported his brother’s position so the Land Reform team reported them both to the county authorities, who charged them with the crime of ‘sabotaging the Land Reform Movement’. Both brothers were sentenced to time in prison. Xia Kekuan served one year, while his brother ended up spending over a decade in a Reform Through Labor camp in Liuzhou. He was finally released in 1962. Two years later he was officially rehabilitated, his Party membership was restored and he was allowed to return to his old job at the hardware company.

After his father and uncle’s imprisonment, Xia Chunlin’s mother, left destitute and declining in health, died in 1952. Not long after, his grandmother passed away too, leaving his Aunt Lichu to single-handedly raise the family’s children. When Xia Kekuan was released from prison, he, together with his sister-in-law, worked the land in order to feed themselves and the family’s five children. Eventually, when they could no longer make ends meet, they sent the children to live in Pingle Town with their aunt Xia Lansu.

The Killing Begins

In 1968, between the months of July and September, five of Xia Chunlin’s relatives were murdered.

Xia Jingsheng, serving as a grassroots Party member, responded to Chairman Mao’s instructions urging cadres to “support the revolutionary actions of the Red Guards” by enthusiastically engaging in the activities of the Cultural Revolution. In 1967, after the January Revolution in Shanghai, where rebel factions of Red Guards had seized power from the central government, he joined Pingle Town’s ‘Revolutionary Rebel Army’, a small group allied with the ‘Grand Alliance’, the province’s rebel Red Guards.

During the Cultural Revolution in Guangxi there were two competing Red Guard factions, the Grand Alliance and the United Command factions. The United Command faction had the backing of Wei Guoqing, the provincial authorities and local PLA units. In 1967, Mao urged the Party to support the leftist rebel Red Guards in their struggle against the ‘bureaucratic’ provincial party establishment, dispatching troops associated with Lin Biao to support the rebels. This led to large scale armed violence in the streets of Guilin and other cities, essentially a proxy Civil War between rival elements of the Party hierarchy. By 1968, United Command had gained the upper hand and began arresting members of the Grand Alliance, forcing them to scatter into the countryside. By the start of August, facing total defeat, members of the Grand Alliance in Guilin had surrendered their weapons and closed down their headquarters.

On the 26th of August, Wei Guoqing, seemingly following the instructions of Mao, replaced the conventional party structure with ‘Revolutionary Committees’. By the start of September, the Pingle Revolutionary Committee had established a Bandit Suppression Unit to hunt down the Grand Alliance members, now officially classified as ‘bandits’, who’d fled into the countryside. On the 9th of September, Liang Peide, a Forestry Department cadre, and one of the local leaders of the United Command faction, led the Bandit Suppression Unit to the Fenyanshan area of Pingle County to capture Xia Jingsheng. When they found him, Xia Chunlin’s uncle was immediately gunned down in a hail of bullets. He was 52 years old.

Xia Chunlin’s father, Xia Kekuan, continued tilling the fields during the Cultural Revolution, never getting involved with any of the Red Guard factions. But due to his brother’s affiliations he was also targeted. One day, members of United Command captured him and brought him to Pingle Town where he was executed. He was 49 years old.

Xia Chunlin’s elder brother, Xia Shaoqing, like his uncle, also joined the local ‘Revolutionary Rebel Army’. He was also captured and executed by the United Command faction. He was 30 years old.

Xia Chunlin’s other elder brother, Xia Shaode, worked alongside Xia Shaoqing, and was also a member of the rebel faction. To earn a living, he and a number of young workers often travelled to Guilin to work jobs. During the outbreak of armed conflict, the United Command beseiged the city, preventing him from returning to Pingle. For his own safety he and his friends took refuge in the area of the city controlled by the Grand Alliance. After the Grand Alliance surrendered their weapons, Xia Shaode was captured and brought back to Pingle, where he was shot dead. He was 25 years old.

When the Cultural Revolution began, his younger brother, Xia Shaoxi, was in the third grade at Pingle Middle School. He joined the school’s rebel faction, and took part in the activities of the time: going to meetings, writing ‘big character posters’, traveling freely around the province and neighboring areas with his friends. After the Grand Alliance were crushed in Guilin, he was forced to flee to the countryside, where he survived for several days in the mountains, but crippling hunger drove him into the fields in a search for food, where he was captured and brought back to Pingle Town. They shot him by the side of the road and dumped his body in an abandoned lime kiln. He was 19 years old.

Two members of Xia Chunlin’s extended family were also murdered: Xia Keshun and Xia Shaoqun. Both were hardworking peasant farmers who never got involved with the factional struggles of the Cultural Revolution. They were killed merely because a spiteful neighbor exploited the political situation to avenge a prior dispute he had with the two.

And just like that seven members of Xia Chunlin’s family lost their lives. At the time not only were there no governmental bodies to look into the killings, but in actual fact it was the actions of the authorities that made it possible for people to believe that these killings were justified. It was the inevitable consequence of their propaganda.

A Political Analysis of The Pingle Massacre

While the killings were, of course, the result of Chairman Mao launching of the Cultural Revolution. The main reason the violence in Guangxi was so widespread and why it manifested itself in such a gruesome and barbaric manner was due to the actions of the most powerful man in the province, Wei Guoqing. As a high ranking cadre of the Communist Party, he had in his hands the collective provincial powers of the Party, the state and the army. His underlings hailed him as ‘The Most Excellent Son of the Zhuang People’. In reality, he was a despot, a sadistic tyrant, a butcher stained with the blood of the Guangxi masses.

During the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, Wei Guoqing suffered at the hands of the Grand Alliance. In both Nanning and Guilin he was the target of struggle sessions, and forced to wear a dunce cap. These incidents were the consequence of Mao Zedong’s rhetoric. It was Mao who encouraged young students to rise up and rebel against the ‘capitalists’, ‘party bureaucrats’ and ‘revisionists’ in the Party. Unsurprisingly, from this time on, Wei Guoqing held a grudge against the rebels.

Wei and the authorities under his control supported and encouraged the United Command faction’s repression of the Grand Alliance. In response, the Grand Alliance became ever more resolute in their desire to overthrow Wei and his allies.

In 1967, Mao began to openly support the rebel factions across China, he called for the PLA to defend the rebels against the factions backed by the provincial authorities. As a result, in November of that year, Wei was forced to submit a self-criticism to the Central Committee in Beijing, acknowledging the error of ‘backing one Red Guard faction while suppressing another’ and ‘inciting the masses against the masses’. He humbly apologized to Mao and the victimized rebel faction. But it was later proven that his apology was merely a stalling tactic to hoodwink the people of Guangxi while he waited for the opportunity to retaliate.

That same month, representatives from Guangxi’s two Red Guard factions arrived in Beijing in order to negotiate a peace agreement, presided over by the Central Committee. Meanwhile, the Central Committee distributed a report to its lower level cadres, titled ‘Decision on How to Solve the Guangxi Problem’, declaring that Wei had been installed as head of the ‘Guangxi Revolutionary Preparatory Group’, to mediate disputes between Red Guard factions.

At this point, if Wei had been able to work in the public’s interests, maintaining an impartial position that treated both factions equally, it’s very likely that the inhuman violence that broke out cross the province would never have occurred. However, even though both parties had ostensibly achieved parity, the situation began to detoriate at an alarming rate. The simple reason was that Wei Guoqing and his allies, concerned that their own self interest was at risk, were absolutely terrified of the ‘ultra-leftist’ Grand Alliance. Their hostility toward these rebels was so overwhelming that nothing short of total annihilation would satisfy them.

They continued to support the United Command faction and suppress the Grand Alliance. Party cadres who defended the Grand Alliance were viciously slandered and smeared as the “capitalists, turncoats, spies and conspirators”, they were accused of conspiring to “seize the power of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat” turning it into the “Dictatorship of the Capitalist Class”. Therefore they had to be crushed.

Mere weeks after Wei had apologized to Mao, the authorities and armed forces in Guangxi began to openly support the United Command faction and encircle the rebels. In many locations across the province, Grand Alliance members were forced to flee either to the countryside or to the cities still possessing rebel strongholds.

From January 1968 until April, the Revolutionary Councils established across the province only served to accelerate the victory of one faction over another. Defeated rebels fled to the remaining Grand Alliance strongholds in Nanning, Liuzhou and Guilin.

It was under such desperate circumstances that the desperate rebels in the three big cities seized weapons from the army in order to defend themselves from the United Command factions besieging the cities. This moved played right into the hands of Wei Guoqing, who immediately launched a propaganda blitz accusing the rebels of “Opposing the newly created Revolutionary Councils”. He called the three big cities “Fortresses of counterrevolution”, infested with traitors, spies and unrepentant capitalists who represented the “lingering elements of the Kuomintang”. Wei called on the ‘revolutionary proletariat’ to unite in thoroughly eradicating them.

Wei Guoqing’s government then had the Grand Alliance faction officially classified as counterrevolutionaries, resulting in widespread arrests, assaults and killings. As this was going on, Wei Guoqing and his allies lied about the situation to the central government in Beijing, framing the self-defense of Grand Alliance members as ‘a counterrevolutionary uprising’. In response, the Central Committee under the direction of Mao Zedong issued the ‘July 3 Public Notice’, aimed specifically at the crisis in Guangxi, demanding the immediate halt of all armed conflict.

On the 25th of July, representatives from both factions met with members of the Central Committee in Beijing to resolve the crisis. The Central Committee twisted the facts in order to place the blame solely on the Grand Alliance. As a result, for three months, from July to September, the entire province of Guangxi rained blood. Captured members of the Grand Alliance were publicly executed. They were shot to death, stabbed to death, beaten to death with sticks, their skulls were crushed with rocks, they were drowned, they were burned alive, they were raped, and some were even eaten.

It was against this backdrop of political fanaticism and brutal armed conflict that the Pingle Massacre unfolded. This savagery and hysteria was stoked by the Chinese government, a national disgrace!

Aftermath

After the factional struggle had finally ended toward the end of 1968, Wei Guoqing and his underlings made sure to strictly forbid all mention of the killings. Those who dared expose the extent of the violence were arrested and tried as ‘active counterrevolutionaries’ . After Mao’s death and the downfall of the Gang of Four, Wei Guoqing began blaming the violence in Guangxi on the Gang of Four and their provincial allies. However it’s impossible to conceal the truth forever. In the more liberalized political atmosphere after Mao’s death, a large number of victims began to speak out, defying censorship, they bravely exposed the heinous crimes of Wei Guoqing and his murderous commanders.

The Central Committee, with Hu Yaobang as General Secretary, finally learned the truth about the killings in Guangxi, and by 1982, after having dispatched an investigation team to the province, began uncovering the real history of this traumatic period. Their official investigation revealed that over 1900 people were killed in Pingle County, among them: 221 party cadres, 155 workers and 1446 peasants and villagers, primarily those accused of being landlords, rightists or counterrevolutionaries.

Of the killers, only 50 were brought to justice, verdicts included: 1 death sentence, 2 life sentences and 47 prison sentences of between 4 and 15 years. An additional 1115 people avoided legal prosecution and received inner Party discipline instead: some were expelled from the Party, others were downgraded in rank. Many others avoided all punishment whatsoever.

While for relatives of victims, this outcome was extremely unsatisfactory, there were a few signs of progress: the Party officially condemned the actions of the Guangxi government and reversed the charges against the wrongfully accussed, including the five surviving members of Xia Chulin’s family

However, Xia Chunlin believes that only by establishing a constitutional democracy governed by the Rule of law can the Chinese people fully resolve the problems that led to the Cultural Revolution in the first place, and prevent such barbarism from ever occurring again.