I was about to sail from Takao to Amoy on the other side of the Taiwan Strait. The sky was overcast. On the hill by the port, a red flag swished atop a towering flagpole. It had just been raised, forecasting stormy weather. The sea in the bay was calm, but looking up at that silent, drooping flag, I couldn’t help but feel a little apprehensive. I asked a steward, who’d come up to say hello, what he thought about the weather.

“Hmm, They say there’s going to be a storm, but at most the journey takes twenty hours, if we set sail today, we’ll avoid it. The storm won’t begin until we’ve already reached the other coast.”

Accompanying me was my guide, Cheng, a student at a dental hospital in Takao opened by an old friend of mine from my middle school days. Cheng lived there with the support of his elder sister’s husband, but he was originally from Amoy. He was born there and had graduated from a middle school in the city. He’d made the journey across the Strait three times already. He told me the sea was calm during the summertime, which alleviated my fears and convinced me to sail.

Since I was already onboard, there was nothing more I could do about it, I might as well try to take it easy. And so, when, after waiting for the ship to start moving, eight or so passengers in the first and second class began to sit down on the deck in rattan chairs, I put on a brave front and joined them. At one point, a rather striking Taiwanese man appeared on deck. The Taiwanese are not foreigners, but Chinese people residing in Taiwan. Since people in Japan are often confused about this simple matter, I felt it worth mentioning.

This individual was a youth in his mid-twenties. Although there were many other Taiwanese onboard, he stood out so conspicuously due to his graceful bearing. He wore a white burlap summer jacket with pleated, buttoned pockets on both breasts and both sides, a belt was wrapped around his waist from the back—the kariginu method,

underneath he wore a light shirt with a long, black satin necktie. White linen kariginu were really quite exquisite, but what’s more, standing there on the deck, he wore a pair of black riding boots, pulled three inches above the knee. On his head, even more curiously—he wore a one foot wide, brimmed, high-topped Taiwanese Panama hat, looking like something out of a Western movie. Underneath, his hair was long, thick and glossy. His eyes were framed in a pair of big, round spectacles with dark green lenses. If he was a cheerful sort of character, always smiling, presumably he would look like some kind of goofy traveler. But, for whatever reason, on this young man, these clothes were really quite flattering. He had the characteristic complexion of a Taiwanese — dusky, sun-tanned, I couldn’t tell if he was pockmarked. This slightly grimy, sinister face, combined with those large, dark green glasses, gave one a peculiar impression. It reminded me of a scene in a detective novel where a noticeably suspicious character suddenly appears, his clothing is so incredibly garish, surely as soon as he made a single move, he’d be detected. However, as it turned out, this man and my companion, Cheng, were old acquaintances. They had already begun talking intimately with each other about who knows what.

“This is my friend from Tainan, he’s a businessman.”

“Ahh!?”

Cheng had spoken in English, maybe because the young man couldn’t understand Japanese, either way, the way he spoke, didn’t seem like he was making a cordial introduction. I took a look at the business card this Taiwanese man had just handed me in a courteous manner. His name was Chen. To avoid an awkward silence, and because of the curiosity he had aroused in me, I asked him:

“You’re in business?”

“Mmm, I do business, it’s rice business.”

Even for a Taiwanese, his Japanese was lousy.

“How long do you plan on staying in Amoy?”

“Mmm, I go often.”

“This time, how long will you stay for?”

“Fifteen days about.”

The ship began leaving the port. The port was narrow, leaving less than 30 meters space on each side of the ship. The wind was wild and the waves were high, the hull shook and swayed violently.

My anxiety returned, finally becoming so unbearable that I had to go lie down in my cabin. In no time at all, Cheng came back too. Even though the ship had already left the port, it still swayed frightfully.

“Last night I must have been exhausted…”

“The waves are enormous.”

“Mm-hmm, over the night it’ll have gotten much worse in Taiwan. We only experienced a little bit of the tail end of storm, but I’m sure it still added to your woes! Normally in the summer, the sea is perfectly calm. Oh well, all things considered, we avoided the worst of it.”

As I listened to the ship captain talk, looking down, I watched a quarantine officer step off a small motorboat onto the ship and begin to conduct quarantine inspection for the second and third class passengers. People were lined up on both sides of the lower deck: on the left were third-class travelers; on the right, second-class. The travelers on both sides were all Taiwanese. The aforementioned overdressed youth stood out among the queue of second class passengers. The quarantine officer was a potbellied man almost two meters tall, most likely an Englishman. He wore a helmet and a white uniform with a standing collar. Not long after, he came up to the high deck where we were standing. He looked over everybody, one by one, and then shouted “Okay!” and left.

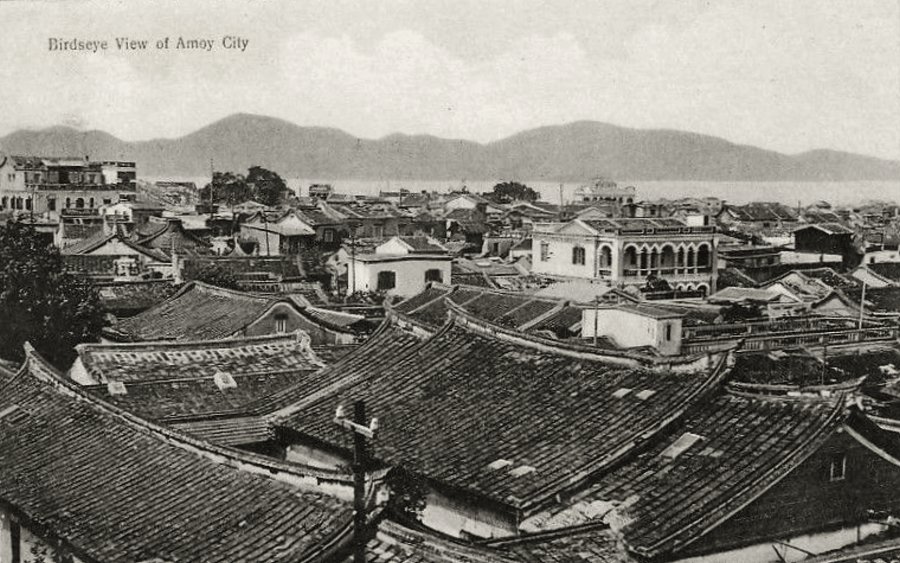

The motorboat departed noisily, cutting through white spray. The sea looked muddy, perhaps because of the overcast sky. Our steamboat had already whistled once, I gazed at the little rocky islets of varying sizes on our left, as we sailed toward the inner recesses of the harbor on the right. As Amoy changed shape it gradually became more vivid. Passing through gigantic exposed rocks, I could see islands rising all around. At the foot of the most precipitous rock stood a row of Western, red brick houses. So, this must be downtown Amoy, a little shabbier than I’d anticipated. The big island on the left must be Kulangsu. At first glance, I thought, Amoy was a bleak, desolate island, Kulangsu was encircled by the dense foliage of green trees.

Cheng was by my side, either talking about something useless or giving me an explanation of what we saw. By now neither his father nor his uncle lived here, but even so, he still felt the joy of returning home, whereas I felt the joy a traveler feels, the novelty of arriving at a new destination.

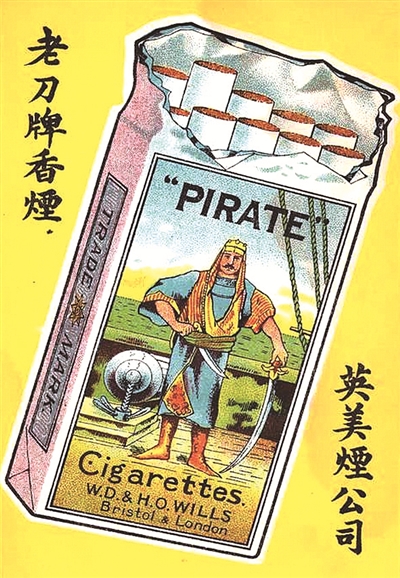

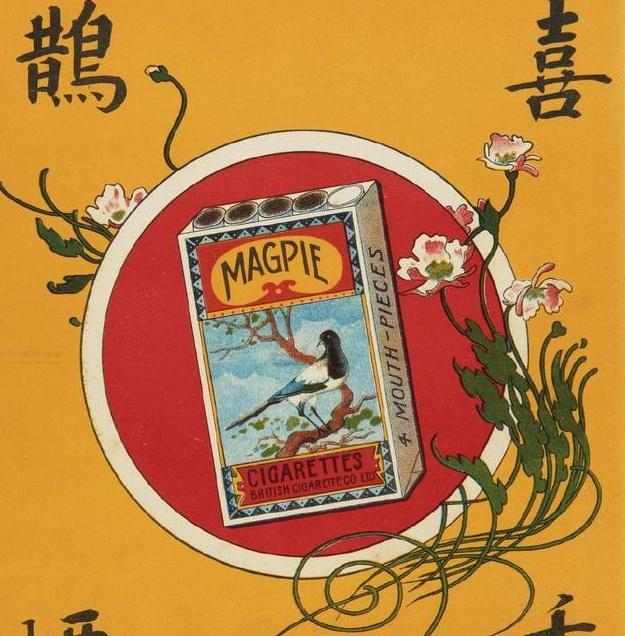

Sampans gathered lazily at the side of the ship. The strong wind made them bounce lightly on waves. I thought I’d lost Cheng lost in the crowd, but then I saw Chen, the young man who looked like he came straight out of a detective novel. He had an affected sober look on his face. Apparently Cheng had went to look for him, and now they stood side by his side. Chen carried a large, red suitcase, Cheng had a straw basket. I carried a black bag. Cheng deftly hopped onto one of the small boats, I jumped next, and then Chen followed. As our sampan moved away from the ship, other passengers on our little boat, eager to get ashore, paddled forward, along the land toward the pier. The foot of the shore’s stone wall was being battered by waves. Right above, stood a house with an ‘Inn’ sign. Almost all the houses were plastered with cigarette advertisements—due to the erosion from the wind and rain, the images and words were faded and mottled. From what remained, I could see pirates, idiots, peacocks, etc. To my surprise I recognized pictures from the cigarette packets my family’s cart puller smoked when I was a child. I hadn’t expected to see anything here that could spark such interesting memories. Not only were the walls covered in cigarette advertisements, but on the towering rock behind the houses, large Chinese characters had been carved, advertising the Pirate cigarette brand. In between the houses on the coast that served as cigarette billboards, a few slightly larger residences were devoid of any such eye-catching imagery. In one of these houses—as I abstractedly look around, I noticed something delightful—a young Chinese girl in a bright, wisteria-colored jacket stepping onto a second floor balcony. She seemed in a light mood, a resplendent smile flowered on her face as she surveyed the ocean scene. Suddenly, she precariously bent her slender upper body over a strange, vinelike railing, and looked down at something below—it looked like she was waving her hand at a monkey playing on the ground below, and then drove it away—a monkey! At least, that’s what I think it was, I instinctively felt so, but why? I don’t know. Actually, it could have been a cat or a dog, I’ve no idea. Just when I wanted to confirm my hunch, our sampan passed the stone wall, obstructing my view of the house. It was a monkey! I was sure of it.

So, this was my first impression of Amoy—this creature being teased by a girl in wisteria —surely it was a monkey. Later on, because I was invited there, I learned that this balcony was a tea garden, part of one of Amoy’s first-class tea houses, the young girl teasing the ‘monkey’ was merely one of the establishment’s many miserable waitresses.

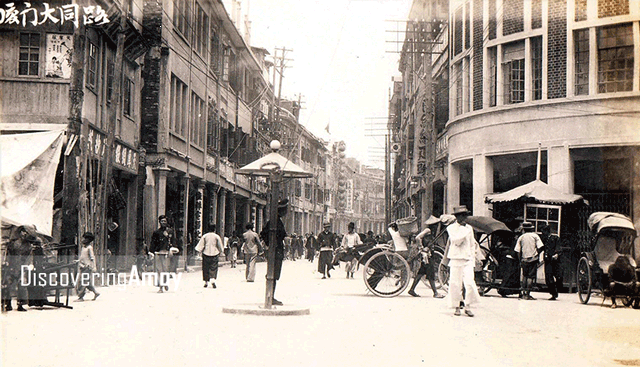

A coolie carried three pieces of luggage—mine, Cheng’s and Chen’s—together we entered a hotel. A man who looked like he might have been the proprietor led us up to a room on the second floor—dim, completely unventilated, nine square meters in size. Cheng and Chen talked about who knows what, then Cheng said something to the proprietor, and instructed the coolie to go back downstairs. “This is the best room they have,” Cheng bluntly informed me. So again stepped back onto the narrow, flagstone road, less than two meters wide . The street was bustling, with many stores in each side. Walking along I saw stores selling meat and fish, as well as stores with old clothes for sale, hanging on the storefront. This, I thought, was probably a second-rate street in Amoy. We encountered a sedan chair as it cut its way through pedestrians, sitting atop was a gentleman in western garb wearing a helmet-shaped hat. Although there’s little difference between them, I still thought he was neither Japanese nor Chinese, something more complicated, for instance, perhaps he was the hybrid offspring of a Malay and a Chinese beauty. He possessed the gaunt face of a scholar, with spare whiskers and a high nose, he was in his late thirties….

As I inspected this stranger, Cheng thudded his way into a house. It was another hotel. After passing through a narrow room more than twenty meters in length, we reached a large room, which looked like a salon or cafeteria. The room contained about ten or so tables with chairs. Many more chairs were lined along two walls, fifteen or so guests were spread around the room, sitting and talking, one person was taking a nap. At the front of the room was what seemed to be an cashier’s office, facing a U-shaped staircase. The house on the street and the hotel were connected by a flat roof, which functioned as an open air terrace. After climbing the staircase, we reached the terrace, and entered the hotel’s lobby. On three sides were guest rooms. The man inside the cashier’s office had let us inspect two of the rooms. The window of the first room was wide open, it faced the terrace, so the room was incredibly bright, but this just made its squalid appearance all the more apparent. The build up of dust on the ceiling had turned it black, the four corners were covered in spider webs. The bed rested against the wall. Below the window, opposite an old four-cornered sandalwood table were two wooden stools and two large chairs. In the center of the wall was some kind of closet that opened at both sides. On the wall, inscribed in large characters were six words, hanging underneath was a poster promoting Magpie cigarettes or some other such brand. The face of a three-color, halftoned Shanghai beauty was already coated in dust.

This was Nanhua Hotel’s finest room. We decided to stay. Each day, besides paying the daily room rate of 1.80 silver dollars, I spent about fifty to seventy dollars. I made them put Cheng’s bed in this room too. His acquaintance, Chen, rented the room opposite ours, separated by the lobby. Our room was about thirteen square meters, Chen’s room was about ten. I ate the local staple fare, pork and an assortment of vegetables pickled in soy sauce. I ate taro porridge, which was just like rice soup, three portions cost about fifteen dollars—according to Cheng.

I took a trip to the Amoy branch of the Niitaki Bank to convert my Japanese money into Chinese currency. The silver dollar had been appreciating in value, so I only exchanged fifty yen. Afterwards, I went with Chen to the Bank of Taiwan branch located nearby the British Customs building on the shore. Even though I know this is a loathsome trait, I still, out of curiosity, watched Chen count out his money—more than thirty notes—about five hundred yuan’s worth of gold coins, plus a few round silver coins—Chen counted them one by one, tossing them on the filing office’s desk, to distinguish by sound the genuine from the counterfeit.

Back at the hotel, a slender sedan chair, looking just like the kind I’d encountered earlier, was resting in the gateway. Just I was about to go up the U-shaped staircase, I noticed the gentleman with the whiskers, who I saw on the street in a sedan chair—a tall, handsome man, standing at the top of the staircase, wiping his forehead with a towel. The staircase was narrow, so he waited at the top, until I’d passed. Apparently this distinctively dressed gentleman was also lodging at the hotel.

On this first evening at the hotel, Cheng told me he planned on going to Kulangsu to visit relatives. He also explained that he’d already sent a letter, in advance of his arrival in Amoy, to his middle school classmate Chou Chun, principal of Yangyuan Elementary School, asking him whether or not he could borrow the school’s room reserved for night staff—because it was summer vacation, it should be vacant. Done talking, he began heading out to handle his affairs. Just as he was about to leave, he told me, “Tonight I’ll be back late, I’ve entrusted Chen to look after you.”

He left around four o’clock. By six o’clock, abandoned, feeling aggrieved and lonesome, I went over to Chen’s room. I pushed the door, but it wouldn’t open, he was probably out. But the door wasn’t locked on the outside, so it must have been locked from the inside. This fellow was probably still asleep. While having these thoughts, I returned to my room and lay down on the bed that looked something like a desk. Now and then, the bellboy came into my room to see if I wanted to order dinner, but knowing that I didn’t understand the language, he quickly left again. There was nothing I could do, right now if Chen was around, we could eat together, I thought, while waiting in the room. But Chen never came. I went onto the terrace, and looked into Chen’s room from the window near the stairs. In the haze of the evening it was impossible to see clearly. By the time I got hold of a lamp and returned to his window—although the light still burned, his black curtains were closed. I’m ashamed to admit that at that moment I needed desperately to go to the bathroom, but I’d no idea where it was. Fortunately just then I spotted the whiskered gentleman on the terrace near my room window, nonchalantly emptying his bladder. I was quite astonished, but then I did the same. Afterwards I learned, here, urination is nothing to hide. After finishing up, I again felt the unbearable pain of hunger. I commanded the bellboy who was just about to come to my room for the tenth time:

“Bring food!”

This is one of the few things I said in Amoy that I somehow remember. Even though my pronunciation was odd, the message seemed to have gotten across. The bellboy said a lot in response, probably asking me what food I wanted. But after having said that one phrase, and having anticipated such a scenario, I’d already made up my mind to remain silent, no matter what was asked, in the end the other party will think of something to bring. As expected, this is what happened. Although I was still a little anxious, I managed to finish my meal. In an indulgent mood I began to reminisce about my hometown.

At about half past eight, Chen finally showed up outside my room – “Sorry!” he said, I thought he said “Silly” . Looking at Chen’s overly earnest face, I got the feeling that he’d just had sex.

“Have you eaten?” I asked.

“Eat.” He replied. With his poor Japanese, I couldn’t tell if he meant he had already eaten or that he was going to eat.

“You had a really good sleep, huh!”

Chen’s expression suggested that he couldn’t comprehend what I was talking about, he said nothing in response other than repeating, Sorry. Because I was lonely, I wanted to keep talking, but he left the doorway of my room. But then he immediately returned and told me “Cheng no return.”

“Hmm, Cheng still isn’t back.” I replied, assuming that’s what he meant.

“No, no, Cheng is now…tomorrow… now…” Chen anxiously waved his hand, “Cheng, Kulangsu, sleep tonight.”

Apparently Cheng had already told Chen that he was spending the night in Kulangsu. And sure enough, that night, Cheng didn’t come back. Although I felt a little uneasy about being left on my own, I was so exhausted that I slept like a rock.

On the second day of my stay at the Nanhua Hotel, around three o’clock in the afternoon, Cheng had still not returned. For breakfast and lunch, Chen visited my room and we ate together. At three o’clock, he again dropped by, dressed once again in his straight out of a detective novel outfit.

“I’m going to a friend,” he said.

Once again I’m left alone—just as I was thinking along these lines, Cheng finally came back.

“I’ve already received permission from Little Chou to rent the room at his school. Tomorrow he’ll send people to come here and pick us up. I also ran into a friend I hadn’t seen in a long time. The waves are wild today, the sky is overcast, there’ll probably be a lot of wind and rain. I heard there’s a storm in Taiwan, after a few days it’ll reach here…”

Cheng prattled on to himself. Originally, I was quite angry with him, but after I saw him and heard that he’d encountered an old friend, I no longer held anything against him. As he spoke, rain fell lightly outside the window. Inside the darkening room, I thought to myself that I should have already turned on the light. At this moment, through the mist came the voices of people climbing the stairs—Chen bringing back two friends. He fumbled with the lock on his room’s door and opened it. After turning on the light, Chen call out to Cheng. Cheng went to Chen’s room and the two spoke for a while. I know it was mainly a result of the language barrier, but I always felt I that I was being treated as an outsider, how could this not upset me? Cheng came back to our room and said, “Let’s have dinner with them.”

Four dishes were laid out inside Chen’s room on a particularly large, round table. The guests were two men in their early thirties, one was well-built, the other was short and fat. The well-built man said his name was Hsieh, he worked in a hospital, what he did specifically, I didn’t ask. The short man was called Ma, he worked at some company. Altogether, the five of us, began eating. They had a lot of beer, more than a dozen bottles sat in the corner. They knew how to drink and they made me drink my share too. When someone wanted to drink, the others, even it was just a sip, had to drink along with him—their own form of etiquette. Because this rule was applied from the very start of the meal, if later on you didn’t comply, they’d force you. Gradually they became more and more inebriated and garrulous.

Both Hsieh and Ma were from Taiwan, but they’d apparently lived in Amoy for some time. Hsieh told me he’d read a lot of books. During our conversation, Cheng, who enjoyed showing off, acted as an interpreter and introduced the pair to me. Through Cheng’s translation, Hsieh told me a great deal, which fascinated me as much as some novels. Nowadays, in terms of literature China is inferior to Japan, but previously they had great literature. Sir, are you interested in history? Chinese history is fascinating, our Records of the Three Kingdoms, the Outlines of the Eighteen Histories, the Spring and Autumn Annals, I’ve read them all, so I know everything. If you ask me anything, you name it, I’ll be able to answer… This Hsieh was truly an overly-attentive fellow. Because he spke so much, it would have been impolite to say nothing. But whenever I said a little, he’d immediately agree and echo whatever I said, excessively polite. He wasn’t just like that with me, but the others too.

It was probably because Hsieh was deliberately trying to flaunt his knowledge that Ma, who was already quite drunk, began intentionally antagonizing him. Even though I’m not educated, I know everything, for example, which establishments in Amoy have prostitutes, which establishments have which kind of prostitues. When it comes to this topic, I can answer any question. As he spoke, he laughed. Because Cheng translated all this for me, I couldn’t help but laugh too. Then Hsieh asked me, Later on this evening, we’ll go together to listen to a couresan sing songs. What do you think? Don’t worry, I wouldn’t take you to a low-down place…

Of course I politely declined his offer. Since I was already slightly drunk, not to mention not being a heavy drinker to begin with, I wasn’t keen on setting out anywhere. Nevertheless, they were intent on taking me out. Seeing that I was looking for any excuse to decline, they grabbed my coat, hat and umbrella from my room and dragged me along. We were going regardless of whether or not I wanted to.

Compared with the uncertainty of being left alone in my room, going out to watch them look for a good time was preferable. So, in the end I conceded. I cautiously watched my step as we made our way along the slippery flagstone road to a house not far away. This was a restaurant with courtesans. They weren’t remotely attractive, and their singing ability for me was neither here nor there. Leaning against a bed in the corner of the room, I used one hand to try to keep my listless body upright, bored stiff, I inexpertly cracked open the watermelon seeds the girls gave me by the handful as I watched a courtesan sing—but I wasn’t listening, I let them sit on my knee, then shooed them away, over to Chen and friends. I was deeply aware of my outsider frame of mind during this experience, quite naturally, I think, my face was sullen. Perhaps out of courtesy to me, they soon decided to leave.

Although the rain was now lighter, it was replaced by a more powerful wind. By this point, they had nothing more to say to a foreigner like me. They spoke in their local vernacular, I had no idea what they saying. Arriving back at the front of the Nanhua Hotel, I hoped that they’d all go inside, but instead they all just stood there. As I unfolded my umbrella, I tried to urge Cheng, as I alone stepped into that long, narrow house. Cheng said a few completely incomprehensible words to his comrades, and then followed me inside. I climbed the U-shaped stairs, which I’ve already described, and came to my room. The effects of the alcohol had already worn off. As I lay my exhausted body on the bed, I noticed how stuffy the room was, and removed my jacket. Cheng didn’t know what to do with himself, he stood, stiff as a post, beside the door. The unconcealed expression on his face suggested he had something on his mind. Finally he said,

“You can sleep on your own.”

“Ah?! What about you?”

“I need to go back out, they said they’re waiting for me, so I’m going right now.”

Cheng left me with these words and departed. That evening, I was left alone in an anxious state to sleep among people who spoke a different language. Thinking about my predicament, I became furious at Cheng’s lack of consideration. Of course, as soon as I didn’t want to go out, I became a nuisance to them, but even so, Cheng failed to show any understanding toward me – a truly thoughtless individual. When it comes down it, his lack of enthusiasm toward me was the reason for his thoughtlessness. In this alien land, without even a familiar face by my side—on top of that there’s the language barrier…. even though it isn’t considered something worth worrying about, their animosity toward the Japanese today was overwhelming, what a place...

After drinking I felt my neuroticism become increasingly uncontrollable. As a matter of fact, right now, regardless of who sneaks in here, no! No matter how arrogantly they swagger in here, no matter how unreasonable their demands—if they want money, I haven’t a penny to give them. I placed my trust in the inherently untrustworthy Cheng, I entrusted all my money to him. At this moment, if any calamity arises, due to the language barrier, neither party can communicate with the other. Under such circumstances, if I were killed, even if my corpse were dumped in the sea, nothing could be done about it… I hysterically imagined such a thing happening, while, for reasons unknown even to myself, I went out into the lobby. I don’t know why but I had the feeling that the bellboy who was bellowing in a characteristically Chinese manner, was cursing at me. I’ve no idea what his problem was, but he remained there, cursing.

I wanted to fall asleep and escape this paranoia, but I only got more agitated. I opened my eyes, and as I turned over, I felt something hard painfully graze my spine. I sat up and turned on the lights that I’d only just turned off. I rolled up the sleeping mat and had a look underneath. I don’t how it was possible but a small, round chunk of bone emerged. After careful inspection, this peculiar thing seemed to be the backbone of a pig. I imagined that this must be some sort of practical joke played by the bellboy or someone else. Perhaps that fellow, who cooks vegetables in the kitchen and teases dogs, found out that I was Japanese and did this. With one foot I kicked the disgusting object under the bed and once again turned off the lights. I couldn’t help but think that the Japanese had a bad reputation here, I was an unwelcome guest—just the day before, walking on the street, I saw all over the walls, slogans like ‘Universal Anger over the Tsingtao Question’, ‘Never Forget The National Humiliation’ etc. There were also slogans about boycotting Japanese goods, ‘Don’t Use the Enemy’s Products’, ‘Prohibit Inferior Goods’. “This fellow is Japanese!”, a drunkard had yelled after colliding with me on the street….

The wind and rain outside showed signs of becoming more violent. Finally, just as I was about to fall asleep, a mosquito made it into my bed. Chinese beds use a gauze curtain, which hangs down at the front, as a mosquito net. I opened the curtain, and waved around the jacket I’d taken off to drive out the mosquito. After doing so, I paid particular attention to the alignment of the net—in order to prevent it from slackening, I used a bag to hold it down at the side—I assumed the mosquitoes were getting in through a gap. Afterwards, I lay down once more. But no more than five minutes later I heard the distinctive humming of a mosquito in my ear. Where were they coming from? I got up and scrutinized every nook and cranny of the bed. It turned out that the gauze on the roof of the bed, which due to dust had a rat-like color, was already in tatters. And so, I admitted defeat. I don’t know at what time I feel asleep, but I suddenly was woken by a clacking sound coming from the heavy bolt on my room’s door.

“Cheng, is that you?”

“It’s me.”

After I opened the door, we exchanged no words, I just went back to bed—I had nothing to say to him. The pocket watch my the bedside showed that it was already half past one. The pig bone was still on the floor.

The next day, Little Chou, the principal of Yangyuan Elementary School, braved the weather and came to visit us. Being a classmate of Cheng, he was also a youth in his mid-twenties. Here, someone who has only graduated middle school is still considered highly educated. Therefore, it seems that by his age, one is qualified to become the principal of a reasonably large elementary school. We left our room at Nanhua Hotel, and went to lodge at his school. Chen, who had slept elsewhere the night before, only returned that afternoon. He’d apparently already discussed plans with Cheng—anyway, they told me nothing—Chen, who it appeared was going to stay with us, still wore that over-the-top outfit, he carried my suitcase, trailing us from behind. A strong wind had blown all night, by the time it stopped, the clouds had disappeared and the rain had ceased. On the sampan to Kulangsu, I cast a sidelong glance at Chen and said to Cheng,

“If the weather is fine, we should go sightseeing, If not, we’ll just have to pass the time somehow.”

“Yes, exactly.”

Although Cheng concurred, looking at the overly serious expression on his face , I could in no way discern what was going on inside his inscrutable head, the same applied to his many compatriots.

Chen, as it turned out, wasn’t staying with us at Yangyuan Elementary, he was just putting luggage there, then going off to I don’t know where. For two consecutive evenings he did not return.

“Where did Chen go?” I asked.

“I don’t know, but he’s likely at the place we went to last time, he’s taken a fancy to one of the girls there.”

“Which girl?”

“Two nights ago, the girl at the house you didn’t go to, she’s an unlicensed prostitute. I only went there to drink, I’d never stay in a place like that, so I returned on my own,” Cheng explained.

Once Chen was no longer around, Cheng became a good guide again. Chen had yet to reappear. Wondering about him, I asked Cheng.

“What exactly is Chen up to? He’s been away for days!”.

“I don’t know”, replied Cheng, “I bet he’s still at that brothel.”

“For all this time?!”

“Yes, I’m certain. He’ll definitely be staying the night there, because he’s an opium smoker.”

As soon as Cheng told me, I thought back to my first night at the Nanhua Hotel, during the hours I was abandoned by Cheng, the Chen who I knew, who locked himself away in his room, who stood in my doorway, staring with a blank, lifeless expression when I unwittingly asked him, “You had a really good sleep huh!” Now I understood his secret.

“Does Amoy have a lot of opium dens?”

“They’re everywhere.”

“I’d love to visit one. Is that possible?”

“To smoke?”

“Not to smoke, just to have a look at the smokers.”

“You can take a look. If you think a place looks interesting, you can quietly enter. If they ask you what you’re doing, you can just leave, it’s no problem. If you’re no good at picking them out, you might have to cover a lot of ground before finding one. These places are filthy, anyone with their own place to stay smokes at home or at a brothel, opium den smokers are all homeless. Their clothes are ragged, some sleep on the floor, they spit everywhere, the walls and the floor are covered in spittle.” To make up for his lack of vocabulary, he screwed up his eyebrows and acted out the action of spitting.

I asked him, “And will you be coming?”

“Mmm, I’ve visited one before, only to have a look, just entering left me dizzy.”

He pretended to be dizzy.

A few days after we had this conversation, Chen suddenly reappeared, carrying a small bag. He must’ve been walking through the school, looking for Cheng. When he ran into me, he asked, “Where’s Cheng?” When Cheng came, Chen left his bag with him and then promptly left. This was the very last time I saw Chen, during the following week or so I lodged at the school, he never again returned. He left two bags in the corner of our room. Their contents remained a mystery.

Later, after I’d already returned to Takou, every time I recalled Chen’s comically over-the-top style of dress, his ingratiating manner that made me uneasy, and his excessively indulgent behavior, I’d ask Cheng,

“How is Chen?”

“I don’t know”, he’d invariably reply.

I don’t know how many times I asked, “Is Chen back yet?”

“I don’t know.”

Once, a few days after saying “I don’t know” again, Cheng remembered something, he took a postcard out of his pocket and told me,

“This was sent from Tainan, where Chen’s mother lives.”

I scanned the postcard written in Chinese, and asked, “His mother will be worried, Is she asking about his address in Amoy?”

“Yes, yes.”

“Did you write back?”

“Already have—I don’t know.”

As previously mentioned, because Cheng couldn’t speak Japanese, his I don’t know’s were always said in English. Because he spoke in English, and because he repeated that same phrase constantly, these I don’t know‘s had a mysterious significance, they always gave me the impression that he employed them ironically, to conceal something he knew.

As for my impressions of Amoy, they’re like fragments of a detective novel I read many years before, most of the plot has already been forgotten.